Compared to Japanese communities in other parts of the U.S., the Japanese population in Texas during the first half of the 20th century was relatively small. In 1910, there were reportedly 340 Japanese people in Texas; by 1920, this number only grew marginally to 449. Still, Japanese immigrants formed close-knit communities as they navigated life in a new country.

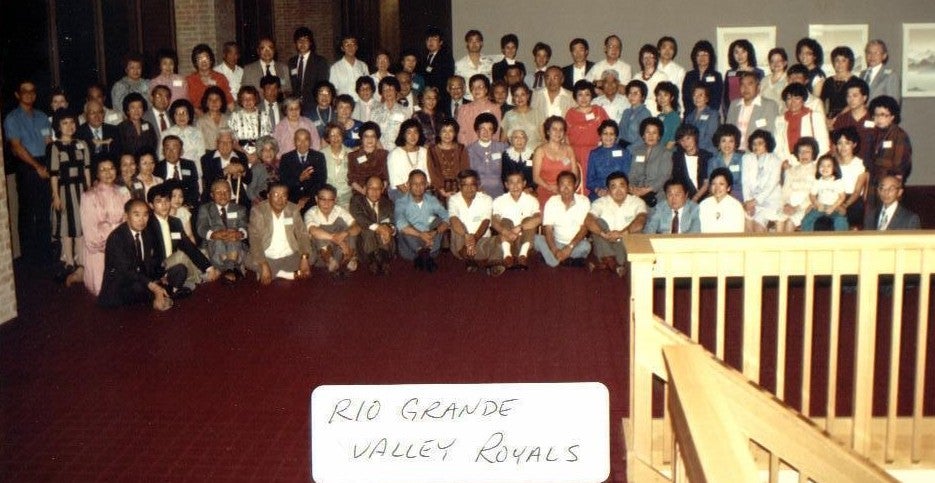

Indeed, while intense anti-Japanese animosity was not particularly prevalent in Texas during this period , like any immigrant community, the Japanese population grappled with culture shock and gradually adjusted to the U.S. In this endeavor, they formed communal spaces and forged ties with one another. One common way through which the Japanese immigrant population did this was through societies and clubs. The Japanese community in the Webster and Houston area, for example, formed the Lone Star Club in 1930, which included the Saibara and the Onishi families. Perhaps inspired by this move, the Japanese in the Rio Valley Grande Valley also formed their own social club called the Rio Grande Valley Royals. Through the club, Japanese people in the Valley hosted community events like picnics with an abundance of Japanese food, as Mary Oyama Hada recalls. The Lone Star Club and the Rio Grande Valley Royals are also said to have formed connections with each other, meeting several times for retreats and excursions.

Religion was also an avenue for community building. On the famous Kishi colony in Terry, for instance, Kichimatsu Kishi, a Christian, built a church, hired pastors, and even taught Sunday school himself in Japanese for those who spoke little English. Meanwhile, in Genoa, where Saburo Arai established nurseries that specialized in fig and orange trees, his wife, Kyoko Arai, managed bible study groups for Japanese women.

When anti-Japanese sentiments did eventually spill over into Texas, the Japanese community banded together. In 1921, following anti-Asian land laws that were being passed across U.S. states, the Texas Legislature debated Senate Bill 142, which would prevent Japanese immigrants from owning or leasing land in the state. As a community primarily focused on farming, Japanese farmers in Texas would be immensely impacted if this act were to pass. They formed Nihonjin-kai (Japanese Association) to strategize their political action and gathered funds for lobbying. Spearheading this group was Saburo Arai, who personally voiced his concern for the Japanese economy to the Texas Legislature. These efforts were not in vain. While the bill made it through Senate, the House amended it to exempt Japanese people who were already living in the state, meaning that only new immigrants would be impacted. These efforts saved the livelihoods of many Japanese farmers in Texas.

Thus, while small in number, the Japanese immigrants in Texas nonetheless established strong community bonds, through which they helped each other adapt to life in America, mobilized political power, and, on the most basic level, felt less isolated in their new home. As the Japanese American community in Texas persists to this day, it is important to look back at this legacy and appreciate the early community-building efforts of Japanese immigrant farmers.